Emergence of incremental technological innovation

ndeed, the intensity of competition leads them to develop innovative products and services. Innovation activity determines the ability of companies to maintain their competitive advantage through offering differentiation

Indeed, the intensity of competition leads them to develop innovative products and services. Innovation activity determines the ability of companies to maintain their competitive advantage through offering differentiation.

Many authors have sought to characterize innovations by their degree of novelty

both for the market and for the company. Among all the aspects under which it is possible to consider innovation, we would like to start with that of change implying progress. According to Peter Drucker, in fact, innovation consists of the determined ized search for change and in the systematic analysis of the opportunities such changes can offer in terms of economic or social progress (Prax, Buisson, et al. 2005 ): innovation is the act of attributing to resources a new capacity to create wealth and disseminating it.

An innovation would thus be an invention that has been accepted by the market, that is to say, a new idea produced but not exploited, not materialized by a product or a service would remain only an invention. Thus, innovation does not appear by chance, but is the fruit of the market's capacity to appropriate new uses, emerging from a dialectic between technical progress and social progress.

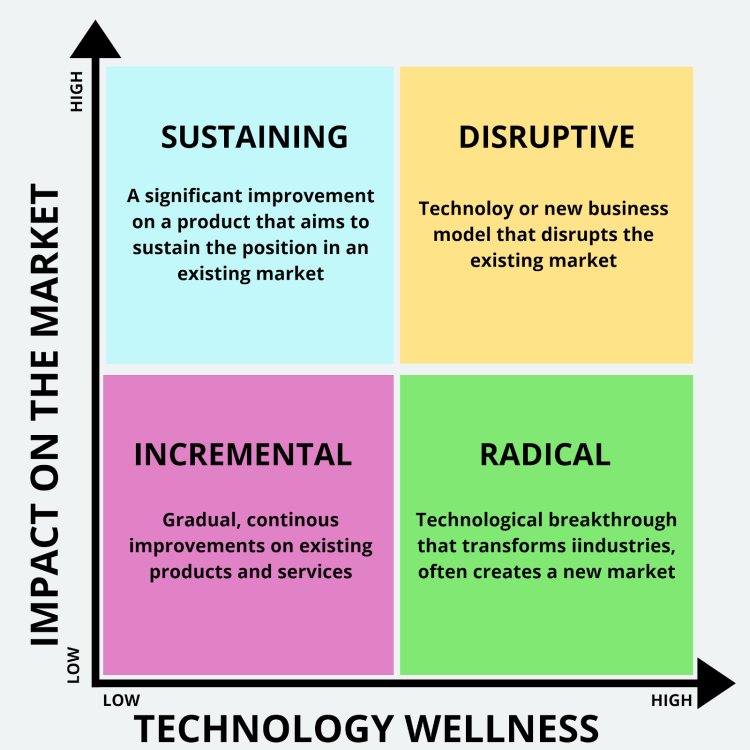

The degree of innovation constitutes another very discriminating dimension of innovation. It is linked to the extent of the change and progress that this innovation will bring about: we are thus accustomed to distinguishing so-called incremental innovation (which does not change the nature of the product or service) from so-called radical innovation (or rupture) which will define a new use requiring new performance criteria.

After this initial point of view on change implying progress, many points of view shed light on the term innovation. Thus, the concept of innovation on the one hand qualifies both a result, an offer of products and/or services, as well as a change in a production process and, on the other hand, refers to multiple fields of research in the areas of firm strategy, marketing or project management (Soparnot, Stevens, 2007). The term innovation is therefore indeed a polyseme, the definition of which varies according to points of view depending on the context in which it is used and which can designate either the process of creation leading to a new element having economic and social value, or the adoption of this element by society, or this element itself (Fernez-Walch, Romon, 2006). These three meanings suggest that innovation only exists about the entity that receives it, that it involves diffusion, and that it is a deliberate act, which leads to the definition below:

We define innovation as a deliberate organizational process, which leads to the proposition and adoption, on a market or within a firm, of a new product (in the sense of AFNOR). This process allows one or more companies to improve their strategic position (conquer or increase market power) and/or strengthen their skills and technologies. The new product can be a physical object, a service, a technology, a new skill, or a combination of several of these variables (Fernez-Walch & Romon 2006 Thus, innovation is not only technological, nor only organizational, nor only commercial, but it integrates the different dimensions.

Our problem will be located in the new field of knowledge-based innovation (Knowledge-Based Innovation or KBI ), arising from the confrontation in an industrial context between the field of innovation and that of knowledge management: l the connection between knowledge and innovation was noted by Dominique Foray who observed that the formation of knowledge-intensive activities in a given sector owes nothing to chance, but that it is essentially dictated by the imperatives of innovation (Foray, 2000). Starting from the observation that the generation of ideas is not taken into account as a mechanism (and even less as a phenomenon), we seek to explore the place of knowledge in the generation of inventive ideas as entry into the innovation procedure: we thus want to show the existing link between knowledge in the sense of knowledge management and ideation in the sense of the creation, formation and sequence of inventive ideas according to an intellectual mechanism which achieves the structuring of a conceptual essence within the framework of a reasoned format (Saulais, 2015b).

Jean-Noël Lhuillier noted that it was essential to measure inventive activity (Lhuillier, 2005), but that no metric existed. In response to this absence, we sought to define a situational criterion by relying on the principle of patentability, that is to say, the generation of industrial property rights. We therefore proposed a situational criterion (Saulais, 2013), describing a situation capable of characterizing the inventive character of an activity, in which the organization is confronted with a technical problem such as:

that it cannot be resolved by a person skilled in the art in the current state of knowledge in the field (scientific and/or technological uncertainty);

that it requires the definition of specific complementary and new exploratory investigation work (inscription in the exploratory field);

that its resolution is accompanied by the creation of significant knowledge substantially enriching the state of knowledge (part of the enrichment of the state of the art of the scientific and technical community).

Thus, the inventive idea is the idea that is capable of generating inventive activity. To go further, we supplemented this pragmatic situational criterion with a conceptual criterion of inventive creation linked to a capacity for epistemic mutation (Saulais, 2014; Saulais, 2015b).

An idea being posed by an individual, and its transformation into new knowledge results from a cycle associating three systems (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996): the individual carrying the idea (whose role is to bring about transformations in the knowledge relating to the domain) – the domain (which corresponds to cultural knowledge, to a repertoire of knowledge associated with a culture considered) – the field (which brings together a set of experts “guardians of the domain” or social institutions, who evaluate, then select, among the new ideas and the productions of individuals, those to be retained). The link between idea and knowledge is therefore established by the principle of validation itself.

Our questioning and therefore the strong hypothesis underlying the problem will focus on the reversibility of the idea-knowledge link, that is to say, the passage from knowledge to the inventive idea, not so much in the result (inventive ideas generated). than in the process of generation itself: in this process, we are not so much interested in its mechanism as in its nature.

11 For practical reasons, we will use as a starting point the knowledge of the organization materialized by transmissible documentary traces, coming individually or collectively from members of the organization. It will therefore be about explicit knowledge (Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1997). We will only be interested in the generation of inventive ideas, from the traces of inventive intellectual productions to be inventoried.

Here we propose a method for generating inventive ideas that draws on the inventive intellectual heritage [1] of the actors. It is an unconventional approach, in line with what is now called “knowledge-based innovation” or Knowledge-Based Innovation (Amidon, 2001).

The research question which is deduced from the general framework of the research problem can therefore be expressed as follows: what epistemic connection can be established between the analysis of the structure of knowledge contained in the inventive intellectual heritage and ideation in the sense of creating inventive knowledge?

According to a conventional vision of knowledge heritage (Ermine, 2007), heritage and capital are confused The knowledge heritage in the company is an intangible capital that is not visible in the organization […] the content of the heritage is disseminated in two components, human and social capital and information capital (Ermine, 2007). From this perspective, information capital refers to colossal masses of information, collected over decades, stored, and disseminated by increasingly sophisticated information systems (Ermine, 2007). Our analysis consisted of separating capital and heritage (Saulais, 2013).

Thus, relying on the Intellectual Property Code, we consider capital as a set of assets capable of generating income and intangible capital as a set of intangible assets (Saulais, 2013). An example of an intangible asset is constituted by a title granting a property right to an invention patent, this title having the characteristic of property (Laperche, 2001). A patent of invention is constituted by intellectual content, which, when recognized as satisfying the conditions of patentability, confers on its inventor a title of property: the intellectual content falls under the heritage and the title of ownership of the capital (Saulais, 2013; Saulais, 2014). Thus, the knowledge heritage, in common sense, is none other than the information heritage (Lhuillier, 2005).

Inventive intellectual heritage can be deduced from the analysis above: dematerialized by nature, it is made up of all the knowledge specific to the actor who carries it, existing or newly created knowledge and formatted from works conceptual ideas likely to generate intellectual property rights (Saulais, 2013; Saulais, 2015b). These rights may fall under the industrial property regime (property titles conferred by patents of invention) or the literary and artistic property regime. Carried by an individual, inventive intellectual heritage is not susceptible to appropriation, which shows that the expression “intellectual heritage of an organization” is a serious misinterpretation and that it must be replaced by the expression “intangible capital”. this intangible capital is constituted by appropriable intangible assets (Saulais, 2013).

This innovation model, which we meet under the names “innovation funnel” or “innovation pipeline”, finds its origins in the development model, Development Funnel, in development project management (Wheelwright, Clark, 1992). According to this model, the innovation procedure consists of a phase called “upstream innovation” (generation of ideas, exploration of concepts, feasibility analysis, and evaluation) and a phase called “downstream innovation” (domain of development).

A recent study by the Knowledge Management Club has summarized numerous operational methods of innovation in firms and shows that all these methods follow approximately the same procedure, summarized in Figure 2 and detailed in (Le Loarne, Bianco, 2009):

the selection of innovation projects is done by choosing the mode of presentation of the projects after defining the internal selection criteria;

deployment is based on the protection, diffusion, and valorization of innovation.

In an industrial context, innovation activities in the technical field are based schematically on two dynamics:

the confrontation with a problem (reduced at a given moment to a technical dimension) leading to an innovative resolution. It is an innovation process in a closed framework: the problem to be solved (Figure 3);

the idea of having found a market. It is an innovation process in an open framework In Figure 3, the framework for thinking is depicted from the outside to the engineering team. The driving force behind stage 1 is the “market”, in the sense of the customer requesting an addition or an improvement, or even a new product, for which specifications often already describe the required addition.

To respond to this problem-solving type request, the engineer must implement an innovative resolution of the problem posed (step 2). To do this, he will look for new ideas to meet the specifications set out (step 3). This principle of innovation dynamics is characteristic of heteronomic functioning (which draws its rules from the outside).

In Figure 4, the thinking framework is depicted from the inside out. Stage 1 starts with an idea, which stage 2 will transform into an innovative product perspective. This perspective becomes an innovation if it finds a market (step 3). This principle of dynamic innovation is characteristic of an autonomous operation, giving itself its own rules: it is the most fruitful, but the least known and the least mastered.

In both cases, innovation activities are based on the production of ideas, ideas which constitute their essential resource. Classic creativity methods are especially suited to the first dynamic of innovation-oriented problem-solving.

Carried out in terms of the procedure for innovation activities, the analysis of the context of the industrial organization serving as support for the illustration described in paragraph 5 made it possible to show that the constitution of portfolios of ideas was not processed by the organization. The functionalities of knowledge management as practiced in the observed organization do not promote creativity which would allow the generation of a portfolio of ideas, that is to say, ideation, as "formation and sequence ideas according to an intellectual mechanism ” (Lalande, 1926). This analysis of the context therefore gives rise to the problem of ideation in the context of industrial organization, seen as the possibility of generating new ideas from existing knowledge assets, to achieve innovation in an open or closed framework. . To do this, it is legitimate to explore the principle illustrated in Figure 4, the driving force of which is the generation of new ideas based on the analysis of existing knowledge assets.

State of the academic art

Fernez-Walch and Romon (2006) discuss eight different conceptual points of view on the progress of the innovation procedure: valorization of technical progress (Bianchi, 1974), adoption of a novelty (Alter, 2000), whirlwind procedure (Callon, Latour, 1985), marketing sequence (Lambin, 1986), political process, transformation of a technical system (Maffin, 1998), project (Declerck, Eymery et al., 1980; Navarre, Schaan et al., 1989 ), learning procedure. Thus, innovation can be a “ collective learning ” procedure (Hatchuel, 1994), “ a collective creation, organized in time and space, to demanding” (Giard, Midler, 1993), “ an open heuristic which brings together, on the one hand, individuals striving towards goals, projecting values and representations and, on the other hand, a physical and social context transformed by the intervention, but which response, surprises and transforms in return the trajectory of the designer ” (Garel, Midler, 1995), a process of “ creating meanings and new knowledge, which are most often of a tacit nature ” (Chanal, 1999).

According to these authors, innovation is nourished by the procedures and processes of discovery and invention, but it is also a deliberate organizational procedure representative of innovation situations that require articulating innovation activities and exploitation activities, with consistency over time according to four phases: the emergence of innovative ideas, the maturation of concepts, the effective launch of an innovative project, the completion of the project. However, we note that the “Emergence of innovative ideas” phase remains a black box whose content is not formalized.

The management of this innovation procedure has multiple dimensions: Tidd, Bessant and Pavitt note that few works deal in an inte,grated manner with the different aspects of innovation (Tidd, Bessant et al., 2006): Peter Drucker introduced this topic in his book Innovation and Entrepreneurship (Drucker, 1985). Paul Trott drew attention to product innovation management (Trott, 2004), Bettina van Stamm (Van Stamm, 2003) and Margaret Bruce (Bruce, Bessants, 2001) emphasized design. Tim Jones

(Jones, 2002) specifically addressed practitioners. Sundbo and Fugelsang developed a largely European vision (Sundbo, Fugelsang 2002), while John Ettie based himself on the experience of certain American firms (Ettie, 1999). Several compilations of works cover this area, the best known of which focuses on the United States (Burgerman, Christensen et al ., 2004). The texts of Dogson and Rothwell (Dogson, Rothwell, 2004), as well as Shavinia (Shavinia, 2003), are more focused on the international scene. The resulting work from the Minnesota Innovation Project (Van de Ven, 1999) provides an excellent overview of this area and the main research themes. For case studies, mention should be made of Baden-Fuller and Pitt (Baden-Fuller, Pitt, 1996), Nayak and Ketteringham (Nayak, Ketteringham, 1986), as well as Bettina van Stamm (Van Stamm, 2003).

The other texts are generally targeted for the most part on a single dimension of innovation management: the management of technological innovation (Dosi, 1988), organizational innovation (Galbraith, Lawler, 1988), product marketing (Gamel, Prahalad, 1994), ... Tidd, Bessant, and Pavitt (Tidd, Bessant, et al ., 2006) also show how firms are inevitably limited in their choice of innovation strategies by their accumulated skills as well as by the opportunities that they are capable of exploiting, which means that they are on technological trajectories.

In addition, a knowledge organization and management approach can be included in the management of the innovation procedure: Debra Amidon (2001) bases the power of innovation on intellectual capital and she considers that this power results from the combination of rapid knowledge sharing and the evolution of new applications.

The author places each of these dimensions in the knowledge economy, where the assets to be managed are made up of knowledge and all the intangible values associated with it and where the architecture of the innovation management system is designed to optimize the use of financial, human and technical resources: performance in the knowledge economy, structures for the exploitation of knowledge, people as knowledge actors, technology knowledge processing and the knowledge management procedure. This vision leads to a more precise characterization of the contribution of knowledge to the innovation procedure.

Remember that the innovation procedure in the sense of establishing a portfolio of innovation ideas is usually described in four stages (Louafa, Perret, 2008): description of the question, production of divergent ideas, convergence of ideas collected towards the question asked, sorting, and choice.